William Tyndale changed the course of English Christianity – and the English language itself.

Lamenting the lack of Scriptural and theological knowledge throughout churches and even universities, he risked his life to translate Scripture into the language of ordinary people. His printed translation of the New Testament into the common language of England was a major contribution to the English Reformation, and his influence has spanned continents and centuries.

As time was to prove, that is exactly what Tyndale achieved.

After studying the arts at Oxford, he is thought to have spent time at Cambridge, where Lutheran ideas were spreading. This is possibly where Tyndale acquired much of his Protestant convictions. These Protestant convictions would prove to play a major part in his calling.

Gifted and well educated, he could speak several languages and was particularly proficient in both ancient Hebrew and Greek. This knowledge provided him with the skills to be the first person to translate the Greek New Testament into English.

Before Tyndale, the Bible in England was available mainly in Latin, which only priests and educated elites could read. Ordinary people, who spoke English, had to rely on clergy to interpret Scripture for them.

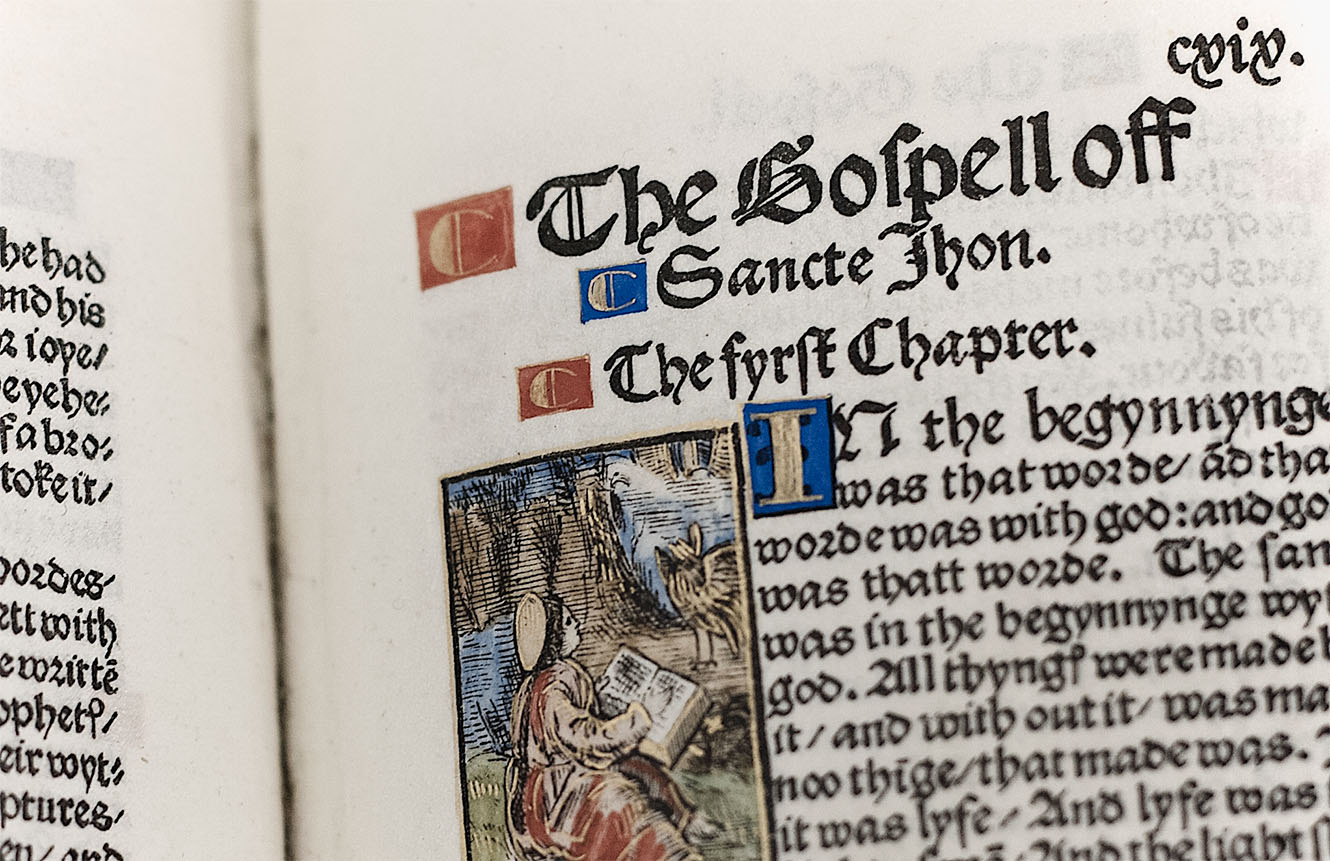

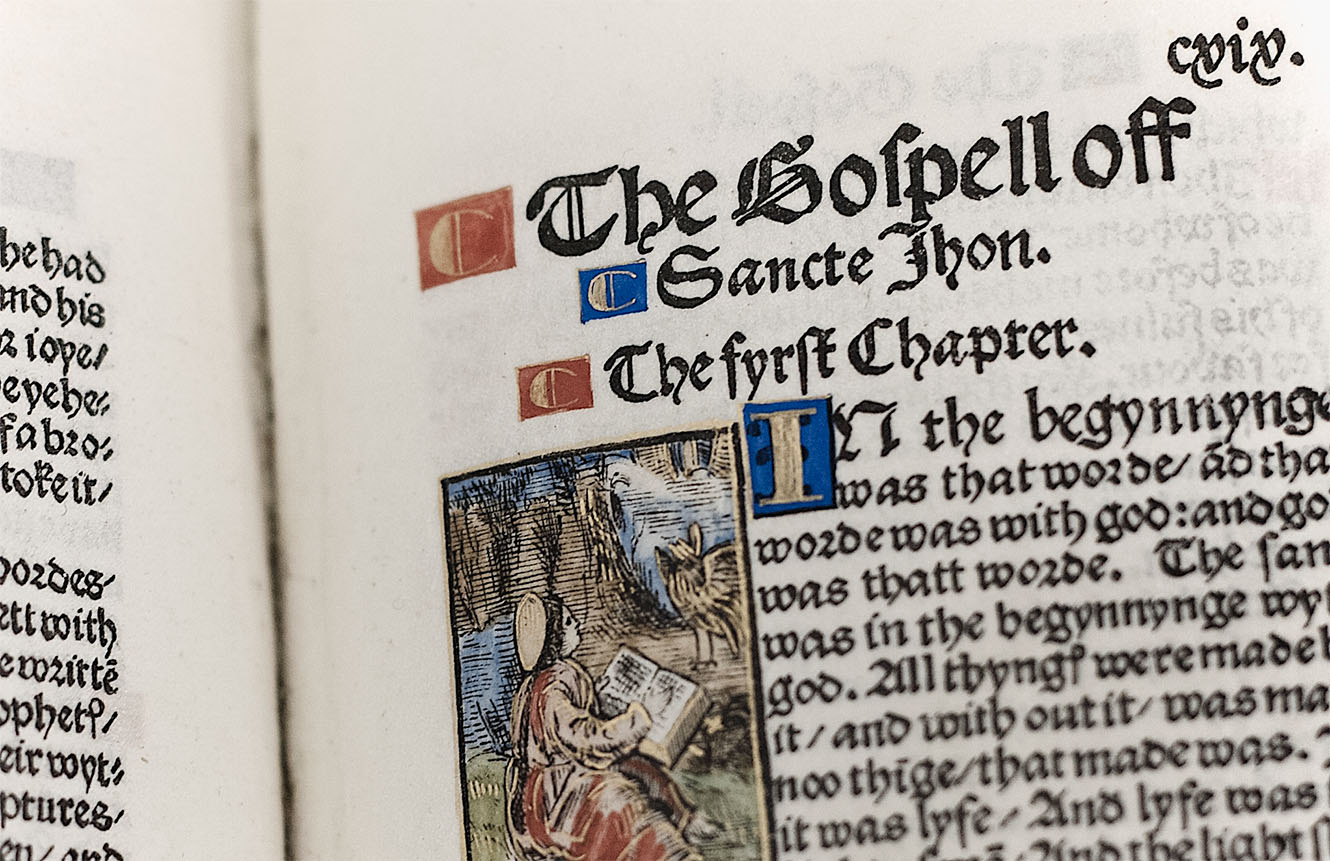

With the aid of recent printing press technology, Tyndale’s first complete New Testament was printed in 1526 and over the next nine years he would continue to revise this translation as well as starting work on translating the Hebrew Old Testament into English. Although he didn’t live to realize his goal of a fully translated Old Testament, he did publish an English translation of the Pentateuch with the help of Miles Coverdale. This partnership proved to be key – in 1535, Coverdale went on to produce the first complete printed version of the English Bible. This paved the way towards a defining moment in English and Reformation history just four years later: the first printed English Bible, authorised by Church and Crown. It was known as “the Great Bible”.

Tyndale’s work leading up to the Great Bible was only the beginning of perhaps the most significant ongoing influence of Bible translation for the next 500 years. Much of the King James Bible – including over 80% of its New Testament – is drawn from Tyndale’s translation.2

William Tyndale had provided the Bible in the common tongue of England for the very first time, and the impact of this spread wider than Bible translation alone. In the year 1500, estimated adult literacy (ability to sign one’s name) sat around a meagre 6% – for comparison, literacy (by those standards) today are at 99% in both England and here in New Zealand.3 Although Tyndale’s New Testament was banned in England, some evidence suggests that many of his fellow English people used his translation to learn how to read.

We still use words and phrases that Tyndale coined today. He invented English words that have since become standard in theology, like “atonement”, meaning at one with God, and “passover”, an English rendering of the Hebrew pesach. He also created phrases that have been adopted into the English language, such as “the powers that be”, “my brother’s keeper”, “the salt of the earth”, and “a law unto themselves”. Even people who have never opened a Bible still use these lines today.4

Beyond translation, Tyndale wrote theological insights to aid people in their understanding of Scripture. To him, this was crucial in counteracting some wrong teaching from the Medieval Church which had influenced England for so long. This concern shows in his opening words of a New Testament preface, “It has pleased God to send to our Englishmen the Scripture in their mother tongue (many of whom genuinely desire it, even though there are in every place false teachers and blind leaders).”5

Tyndale’s theological expositions, as well as his translations, were influential in bringing about significant change.

Such was his criticism at the Church for false doctrine and keeping Scripture from the lay-people, that his English New Testament and other published writings made him essentially a fugitive. He became skilled at avoiding suspicion and often resorted to falsifying publishing details on his printed works to confuse those hunting him.

Tyndale’s work cost him his life. He was betrayed in 1535 while living in Antwerp and executed as a heretic the year after.

Since his death in 1536, William Tyndale’s Bible translation legacy has provided literally millions of people across the world with the Bible in their own language. This was his greatest desire and his ultimate achievement.

1 Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals, A Lane, ed. Timothy Larsen, 2003.

2 How Much of the King James Bible Is William Tyndale’s?, Jon Nielson and Royal Skousen, The Gospel Coalition, 2011.

3 The High Wage Economy of Pre-industrial Britain by The High Wage Economy of Pre-industrial Britain, Robert C. Allen, 2006.

Digital 2020: Global Digital Yearbook, DataReportal.

4 In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture, Alister McGrath, 2001.

5 A Pathway into the Holy Scripture, William Tyndale, 1530.

Check out other articles in the

Characters of our Calendar

series below.

More articles in the

Characters of our Calendar

series are to come.

We have invited these writers to share their experiences, ideas and opinions in the hope that these will provoke thought, challenge you to go deeper and inspire you to put your faith into action. These articles should not be taken as the official view of the Nelson Diocese on any particular matter.

William Tyndale changed the course of English Christianity – and the English language itself.

Lamenting the lack of Scriptural and theological knowledge throughout churches and even universities, he risked his life to translate Scripture into the language of ordinary people. His printed translation of the New Testament into the common language of England was a major contribution to the English Reformation, and his influence has spanned continents and centuries.

As time was to prove, that is exactly what Tyndale achieved.

After studying the arts at Oxford, he is thought to have spent time at Cambridge, where Lutheran ideas were spreading. This is possibly where Tyndale acquired much of his Protestant convictions. These Protestant convictions would prove to play a major part in his calling.

Gifted and well educated, he could speak several languages and was particularly proficient in both ancient Hebrew and Greek. This knowledge provided him with the skills to be the first person to translate the Greek New Testament into English.

Before Tyndale, the Bible in England was available mainly in Latin, which only priests and educated elites could read. Ordinary people, who spoke English, had to rely on clergy to interpret Scripture for them.

With the aid of recent printing press technology, Tyndale’s first complete New Testament was printed in 1526 and over the next nine years he would continue to revise this translation as well as starting work on translating the Hebrew Old Testament into English. Although he didn’t live to realize his goal of a fully translated Old Testament, he did publish an English translation of the Pentateuch with the help of Miles Coverdale. This partnership proved to be key – in 1535, Coverdale went on to produce the first complete printed version of the English Bible. This paved the way towards a defining moment in English and Reformation history just four years later: the first printed English Bible, authorised by Church and Crown. It was known as “the Great Bible”.

Tyndale’s work leading up to the Great Bible was only the beginning of perhaps the most significant ongoing influence of Bible translation for the next 500 years. Much of the King James Bible – including over 80% of its New Testament – is drawn from Tyndale’s translation.2

William Tyndale had provided the Bible in the common tongue of England for the very first time, and the impact of this spread wider than Bible translation alone. In the year 1500, estimated adult literacy (ability to sign one’s name) sat around a meagre 6% – for comparison, literacy (by those standards) today are at 99% in both England and here in New Zealand.3 Although Tyndale’s New Testament was banned in England, some evidence suggests that many of his fellow English people used his translation to learn how to read.

We still use words and phrases that Tyndale coined today. He invented English words that have since become standard in theology, like “atonement”, meaning at one with God, and “passover”, an English rendering of the Hebrew pesach. He also created phrases that have been adopted into the English language, such as “the powers that be”, “my brother’s keeper”, “the salt of the earth”, and “a law unto themselves”. Even people who have never opened a Bible still use these lines today.4

Beyond translation, Tyndale wrote theological insights to aid people in their understanding of Scripture. To him, this was crucial in counteracting some wrong teaching from the Medieval Church which had influenced England for so long. This concern shows in his opening words of a New Testament preface, “It has pleased God to send to our Englishmen the Scripture in their mother tongue (many of whom genuinely desire it, even though there are in every place false teachers and blind leaders).”5

Tyndale’s theological expositions, as well as his translations, were influential in bringing about significant change.

Such was his criticism at the Church for false doctrine and keeping Scripture from the lay-people, that his English New Testament and other published writings made him essentially a fugitive. He became skilled at avoiding suspicion and often resorted to falsifying publishing details on his printed works to confuse those hunting him.

Tyndale’s work cost him his life. He was betrayed in 1535 while living in Antwerp and executed as a heretic the year after.

Since his death in 1536, William Tyndale’s Bible translation legacy has provided literally millions of people across the world with the Bible in their own language. This was his greatest desire and his ultimate achievement.

Check out other articles in the

Characters of our Calendar

series below.

More articles in the

Characters of our Calendar

series are to come.