Tārore was a young girl who was born around 1824 and lived in the Waikato region. Her father, Wiremu Ngākuku, was the rangatira, or chief, of the Ngāti Hauā iwi.

Tārore attended a missionary school run by the Church Missionary Society, which Reverend Alfred Brown and his wife Charlotte opened and ran in April 1835.

Tārore received a Māori translation of the Gospel of Luke, or Te Rongopai o Ruka, from which she learned to read, taught by Charlotte Brown. Tārore carried this precious book in a kete (basket) around her neck. Tārore shared the stories in her precious book with her father, Ngākuku, who at first did not want to listen, but slowly and gradually started to listen to the words of peace from the Gospel.

At the same time, Tārore and Ngākuku’s tribe was in conflict with another tribe, Te Arawa. This threat became so great that Alfred and Charlotte evacuated the missionary school from Matamata to Tauranga in October 1836. While they were leading a group of children along the way, near Wairere falls, a raiding party from Te Arawa attacked the group. While others escaped, Tārore was left where she was sleeping.

She was murdered on 19 October. The precious kete was taken from her neck and the book stolen.

The Māori law determined that utu (revenge) be carried out on Te Arawa, but Ngākuku remembered the words of peace that his precious daughter had shared with him from Te Rongopai o Ruka and told his kinsmen not to seek utu for her death, but to trust in God’s justice instead.

Meanwhile, the kete containing Tārore’s book was taken back to Te Arawa by a rangatira called Uita, but he could not read. He did, however, have a slave called Ripahau who could read, and was invited to read Te Rongopai o Ruka to Te Arawa. After a while, Uita began to take in the words of peace and realised that what he had done in killing this little girl was not right.

Ripahau, on the other hand, eventually left and travelled to Otaki, where he met Tamihana Te Rauparaha, the son of Wiremu Te Rauparaha, who was integral in the bringing of the Christmas Day gospel message in 1814. Ripahau read to Tamihana and his cousin Matene Te Whiwhi and taught them how to read. These warriors took sourced copies of Te Rongopai o Ruka and brought it across the Cook Strait to the South Island and were integral in the spread of the gospel to the South Island.

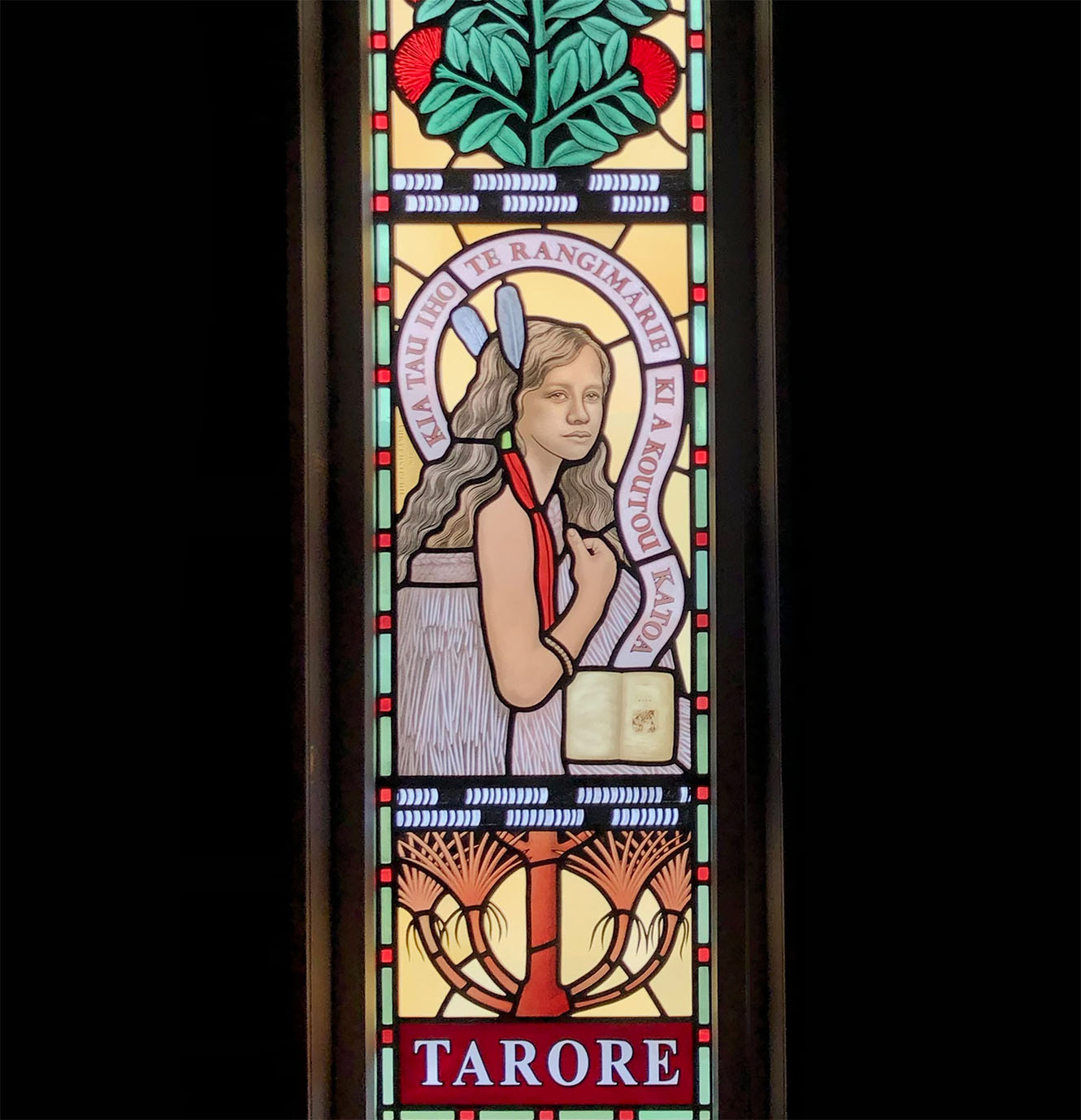

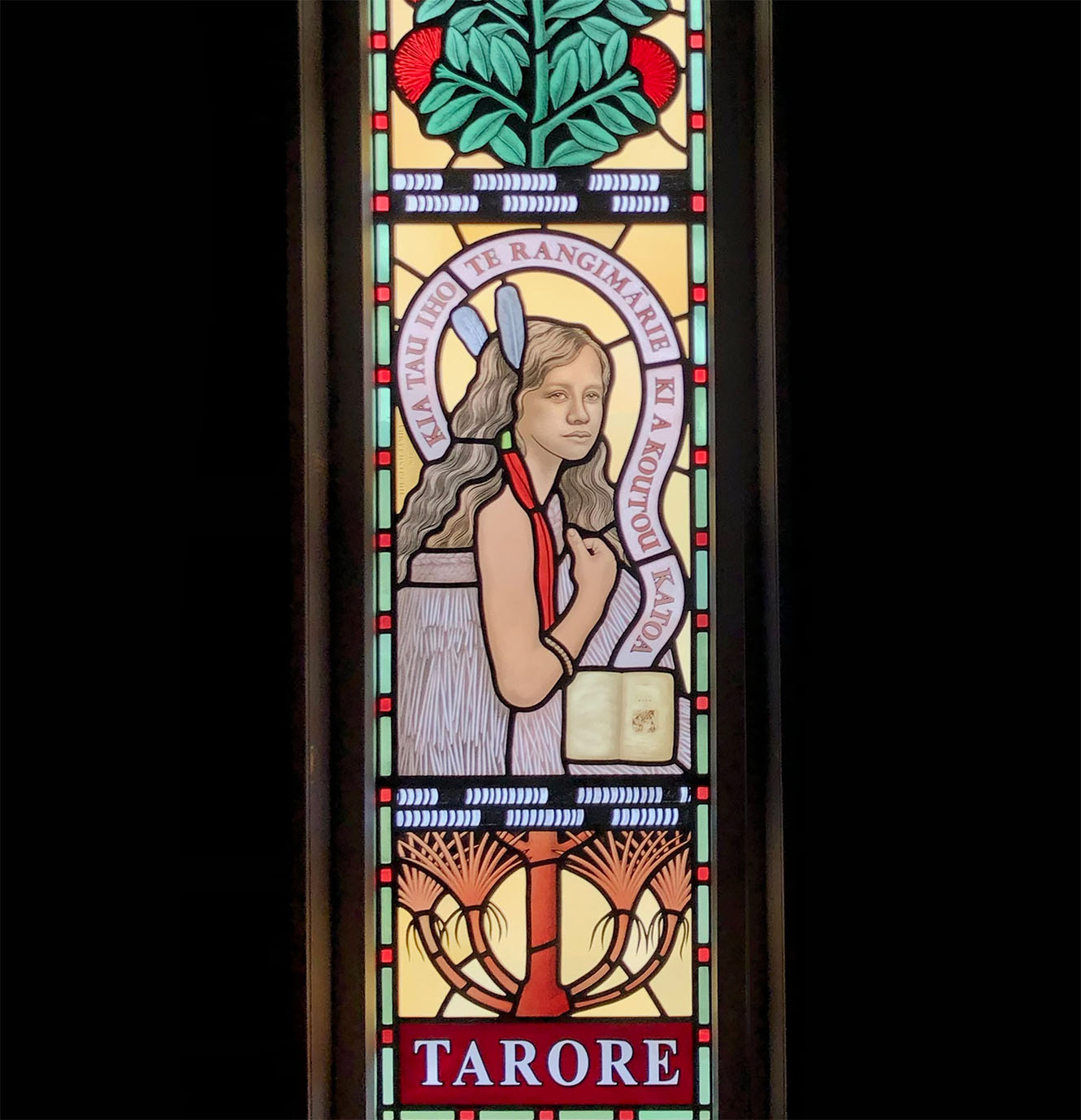

Tārore is buried in Waharoa, where her grave is marked by a fence surrounding it and a white cross. Her death is remembered in the liturgical calendar on 19 October, the day after the feast day of St Luke the Evangelist, whose God-inspired words were used to spread the gospel so widely in Aotearoa New Zealand, making such a significant impact among the Māori people. There is also a stained glass window in St Aidan’s Anglican Church in Auckland, depicting Tārore, with the words “kia tau iho te rangimārie ki a koutou katoa” (peace be with you) around her head.

Tārore’s story of peace has inspired many generations in New Zealand and continues to do so, long after her death. In 2009, award winning author Joy Cowley teamed up with the Bible Society to publish Tārore and Her Book. 240,000 free copies of the book were given to New Zealand primary schools.

“At her tangi, Tārore’s father prayed that vengeance would belong to God; he never gave up hope in divine justice,” the Most Rev Sir David Moxon said.

The impact this one little girl and her small Māori translation of the Gospel of Luke had on New Zealand is great and will not be soon forgotten.

A Pilgrim’s Guide: ‘A Child Shall Lead’: The Story of Tārore of Waharoa, compiled by David Moxon, 2021.

Tarore of Waharoa, St Andrew's Anglican Church Taupō.

Tārore and Her Book, Joy Cowley, 2009.

Check out other articles in the

Characters of our Calendar

series below.

More articles in the

Characters of our Calendar

series are to come.

We have invited these writers to share their experiences, ideas and opinions in the hope that these will provoke thought, challenge you to go deeper and inspire you to put your faith into action. These articles should not be taken as the official view of the Nelson Diocese on any particular matter.

Tārore was a young girl who was born around 1824 and lived in the Waikato region. Her father, Wiremu Ngākuku, was the rangatira, or chief, of the Ngāti Hauā iwi.

Tārore attended a missionary school run by the Church Missionary Society, which Reverend Alfred Brown and his wife Charlotte opened and ran in April 1835.

Tārore received a Māori translation of the Gospel of Luke, or Te Rongopai o Ruka, from which she learned to read, taught by Charlotte Brown. Tārore carried this precious book in a kete (basket) around her neck. Tārore shared the stories in her precious book with her father, Ngākuku, who at first did not want to listen, but slowly and gradually started to listen to the words of peace from the Gospel.

At the same time, Tārore and Ngākuku’s tribe was in conflict with another tribe, Te Arawa. This threat became so great that Alfred and Charlotte evacuated the missionary school from Matamata to Tauranga in October 1836. While they were leading a group of children along the way, near Wairere falls, a raiding party from Te Arawa attacked the group. While others escaped, Tārore was left where she was sleeping.

She was murdered on 19 October. The precious kete was taken from her neck and the book stolen.

The Māori law determined that utu (revenge) be carried out on Te Arawa, but Ngākuku remembered the words of peace that his precious daughter had shared with him from Te Rongopai o Ruka and told his kinsmen not to seek utu for her death, but to trust in God’s justice instead.

Meanwhile, the kete containing Tārore’s book was taken back to Te Arawa by a rangatira called Uita, but he could not read. He did, however, have a slave called Ripahau who could read, and was invited to read Te Rongopai o Ruka to Te Arawa. After a while, Uita began to take in the words of peace and realised that what he had done in killing this little girl was not right.

Ripahau, on the other hand, eventually left and travelled to Otaki, where he met Tamihana Te Rauparaha, the son of Wiremu Te Rauparaha, who was integral in the bringing of the Christmas Day gospel message in 1814. Ripahau read to Tamihana and his cousin Matene Te Whiwhi and taught them how to read. These warriors took sourced copies of Te Rongopai o Ruka and brought it across the Cook Strait to the South Island and were integral in the spread of the gospel to the South Island.

Tārore is buried in Waharoa, where her grave is marked by a fence surrounding it and a white cross. Her death is remembered in the liturgical calendar on 19 October, the day after the feast day of St Luke the Evangelist, whose God-inspired words were used to spread the gospel so widely in Aotearoa New Zealand, making such a significant impact among the Māori people. There is also a stained glass window in St Aidan’s Anglican Church in Auckland, depicting Tārore, with the words “kia tau iho te rangimārie ki a koutou katoa” (peace be with you) around her head.

Tārore’s story of peace has inspired many generations in New Zealand and continues to do so, long after her death. In 2009, award winning author Joy Cowley teamed up with the Bible Society to publish Tārore and Her Book. 240,000 free copies of the book were given to New Zealand primary schools.

“At her tangi, Tārore’s father prayed that vengeance would belong to God; he never gave up hope in divine justice,” the Most Rev Sir David Moxon said.

The impact this one little girl and her small Māori translation of the Gospel of Luke had on New Zealand is great and will not be soon forgotten.

Check out other articles in the

Characters of our Calendar

series below.

More articles in the

Characters of our Calendar

series are to come.